In a world increasingly defined by digital information, China is aggressively pioneering a revolutionary state-driven approach that redefines data not as a private concern but as a core “production factor” on par with land, labor, and capital. This paradigm shift recasts data as a strategic national asset, a raw material to be cultivated, securitized, and traded to fuel economic growth and technological supremacy. This is not merely a theoretical exercise; it is an operational reality backed by a comprehensive national policy, a sophisticated technical infrastructure, and a clear legal framework. For international corporations, AI developers, and global policymakers, understanding this distinct and rapidly maturing model is no longer an academic curiosity but an urgent operational necessity. It fundamentally alters the rules of engagement, shaping everything from compliance obligations and technical architecture design to the very feasibility of accessing one of the world’s largest and most valuable data pools for training the next generation of advanced AI models.

A State-Led Economic Vision

The central pillar supporting China’s entire data strategy is the indispensable and orchestrating role of the state in engineering a new national data economy. The government’s interventionist stance is rooted in a diagnosis of profound market failure, concluding that immense and valuable data resources remain trapped in isolated, non-communicating silos within government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and private technology giants, thereby stifling national economic progress and innovation. In response, the state has positioned itself not as a passive observer but as the primary architect, coordinator, and regulator of a data market designed to serve national strategic goals. This approach deliberately sidesteps the laissez-faire principles that dominate Western discourse, opting instead for direct and forceful intervention to break down institutional barriers, standardize data practices, and create the conditions for a vibrant, nationally coordinated data marketplace. The objective is to proactively manage the flow and allocation of data to maximize its contribution to the nation’s economic output, a stark departure from models that prioritize market-driven discovery and individual enterprise.

This state-centric model deliberately prioritizes the collective economic benefit derived from data over the fragmented, individual-centric control common in Western legal frameworks. This guiding philosophy explains a series of distinctive and often challenging policy choices for multinational firms, including mandatory data localization for specific categories, which requires certain data to be stored within China’s borders. It also underpins the stringent, government-led security assessments that are a prerequisite for most cross-border data transfers, creating a tightly controlled gateway for information leaving the country. Perhaps most significantly, it drives the national push to formally recognize data as a tangible asset on corporate balance sheets, a move that solidifies its economic importance and facilitates its use as collateral. This concerted, top-down strategy is designed to solve complex coordination problems—from breaking down data silos to establishing clear pricing mechanisms—not through emergent market forces, but through a unified and deliberate national strategy aimed at transforming data into a cornerstone of the modern Chinese economy.

The Pillars of a New Data Infrastructure

China’s ambitious strategy is being constructed upon three deeply interconnected pillars: a groundbreaking legal and policy framework that redefines data value, a sophisticated technical infrastructure engineered for secure data circulation, and the direct application of these systems to accelerate the nation’s dominance in artificial intelligence. Each of these pillars is being developed with remarkable speed and strategic clarity, working in concert to create a powerful, unified, and state-supervised data ecosystem. The legal bedrock of this new system is the “Twenty Provisions on Data,” a landmark policy that ingeniously bypasses the complex and philosophically fraught Western legal debate over data “ownership.” Given that data can be infinitely replicated and used by multiple parties simultaneously, establishing a single owner is legally contentious. Instead, the provisions introduce the principle of “structural separation” of property rights, unbundling them into three distinct and tradable categories: the right to hold data, the right to process data for specific purposes, and the right to operate and derive commercial value from data-driven products and services. This pragmatic framework is a masterstroke, as it facilitates market transactions and encourages inter-organizational collaboration by allowing different entities to hold different rights simultaneously, thereby unlocking data’s value without requiring the transfer of the sensitive raw data itself.

This foundational legal innovation is powerfully reinforced by a concurrent financial one. As of early 2024, China’s Ministry of Finance officially implemented the world’s first national accounting regulations that permit enterprises to formally recognize and record eligible data resources as tangible assets on their balance sheets. This allows data to be categorized either as inventory, if intended for sale, or as an intangible asset, if used internally to provide services. This formal accounting treatment is a critical step toward the full financialization of data, transforming an abstract resource into a bankable asset that can be valued, leveraged, and traded. Overseeing this entire ecosystem is the National Data Administration, a central government body established to coordinate data development and circulation. This new agency works in tandem with the powerful Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which retains ultimate control over data security. This division of labor explicitly acknowledges and seeks to manage the inherent tension between the national goals of promoting open data flows for economic growth and maintaining strict control for national security, creating a system of checks and balances at the heart of the data economy.

Technical Architecture for Secure Data Circulation

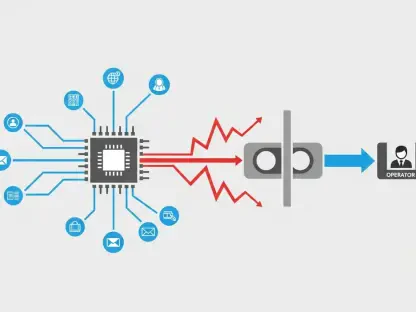

To operationalize its ambitious policy goals, China is systematically building a multi-layered technical infrastructure founded on the guiding principle that data’s value can be fully utilized while the underlying raw, sensitive records remain “available but invisible.” The first layer of this architecture consists of a growing network of state-supported data exchanges, with prominent examples in Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen serving as national models. These platforms are far more than simple marketplaces for data products; they function as integrated compliance and governance hubs. Their responsibilities include formally registering data products, meticulously verifying metadata and usage rights to ensure legitimacy, and programmatically implementing the “separation of three rights” framework. Crucially, they also embed third-party security audits and compliance checks directly into the transaction process, creating a regulated and transparent environment for data commerce. The Shanghai Data Exchange, for instance, even includes an international section designed to facilitate cross-border data trade under this new, highly regulated model.

The deeper, enabling layers of this infrastructure are constructed upon advanced Privacy-Preserving Computing (PPC) platforms and the concept of trusted data spaces. China has actively fostered the development of industrial-grade, open-source PPC technologies, with platforms like WeBank’s FATE and Ant Group’s SecretFlow emerging as leading examples. These toolkits provide a powerful suite of technologies, including federated learning, which allows multiple parties to collaboratively train AI models on their respective datasets without ever centralizing or sharing raw data. They also incorporate secure multi-party computation, which enables joint calculations on private inputs, and trusted execution environments, which use hardware-based isolation to protect data during processing. The third and most advanced layer is the creation of trusted data spaces, envisioned as the core production infrastructure for secure data flow. These are highly regulated digital environments embedded with smart contracts that feature automatic compliance execution, real-time monitoring of data usage, and complete, blockchain-based audit trails for ultimate traceability. The National Data Administration’s ambitious goal to establish over 100 such spaces by 2028 signals a massive national investment in this secure and controlled method of data sharing.

The Symbiotic Relationship with Artificial Intelligence

This entire data infrastructure is deeply and inextricably intertwined with China’s overarching ambitions to lead the world in artificial intelligence. The state is not merely a regulator but an active participant in sourcing and curating the high-quality training data essential for developing powerful large language models. National initiatives, such as the Beijing International Big Data Exchange’s “AI Alchemy Project” and Shanghai’s establishment of a dedicated government-led company to collect AI corpora, are designed to amass strategic datasets in critical sectors like finance, advanced manufacturing, and healthcare. These efforts aim to provide Chinese AI developers with a decisive advantage in data quality and volume, directly fueling the development of next-generation AI applications tailored to the national economy. This state-led curation process ensures that AI development aligns with strategic industrial policy, creating a powerful feedback loop where the data infrastructure strengthens AI, and AI, in turn, generates more valuable data.

Simultaneously, the government has moved swiftly to govern this burgeoning field. The “Interim Measures for the Administration of Generative AI Services,” which came into effect in 2023, represents the world’s first national regulation specifically targeting this technology. It mandates that all training data must be legally sourced and must respect intellectual property and personal information rights, placing a heavy compliance burden on model developers. Furthermore, a suite of binding national standards, set to take effect in late 2025, will codify detailed technical requirements for data pre-training, service security, and data annotation, further standardizing and regulating the AI development lifecycle. In this tightly controlled environment, Privacy-Preserving Computing technologies serve as the crucial bridge that allows AI innovation to proceed in a compliant manner. Federated learning, for example, enables hospitals to collaboratively build powerful medical AI models without sharing sensitive patient records, while secure multi-party computation allows financial institutions to jointly assess credit risk without revealing proprietary customer data. This approach was inadvertently stress-tested by U.S. export controls on high-end GPUs, which compelled Chinese firms to master distributed training across heterogeneous hardware, proving the scalability of privacy-preserving, decentralized AI architectures.

A Fundamental Ideological Divide

The divergence between China’s data governance model and the prevailing Western approach, best exemplified by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), is rooted in a fundamental ideological chasm. The EU’s framework is unapologetically rights-based and human-centric. It views data privacy as an essential extension of individual autonomy and is designed primarily to protect citizens from the potential overreach of both corporate and state power. In this paradigm, personal data is considered to belong to the individual, and the entire regulatory apparatus—including strict consent mechanisms, the principle of purpose limitation, and requirements for data minimization—is constructed to uphold and enforce this individual control. The GDPR’s primary function is protective, creating a shield for the individual against the data-gathering ambitions of larger entities and ensuring that personal information is not used in ways that could harm or disenfranchise the data subject. This philosophy places the rights and dignity of the individual at the absolute center of the data universe.

In stark contrast, China’s model is driven by industrial policy and is resolutely state-centric. It approaches data not through the lens of individual rights but as a strategic national resource whose immense economic potential is currently being squandered due to market inefficiencies like data siloing. Consequently, the primary role of the state is not protection but allocation—actively guiding data flows to sectors and applications where they can generate the maximum economic value for the nation as a whole. While individual rights are addressed in laws like the Personal Information Protection Law, these rights are explicitly situated within a broader framework that prioritizes the productive potential of data as a collective national asset. This fundamental difference in philosophy explains why multinational companies operating in China are confronted with a “dual-stack” compliance reality. They are compelled to maintain a separate, localized IT architecture to navigate a complex web of overlapping laws governing cybersecurity, data security, and personal information, all of which are built upon a set of assumptions about the relationship between the individual, the corporation, and the state that is fundamentally different from that in the West.

Navigating the New Data Superpower

The emergence of China’s comprehensive data-as-asset ecosystem has imposed a specific and non-negotiable set of technical and operational requirements on any company developing or deploying AI within its borders. A mandatory and robust data traceability system became an absolute necessity, capable of meticulously recording the provenance of all training data, maintaining verifiable consent records, and accurately identifying “important data” that requires explicit government approval for any cross-border transfer. Firms also found it essential to implement a comprehensive content security infrastructure, including sophisticated tools for filtering prohibited content from model outputs in real-time and complying with the Cyberspace Administration of China’s mandatory algorithm filing and registration system. Ultimately, building privacy-preserving data pipelines using technologies like federated learning and secure multi-party computation transitioned from being merely a compliance measure to a core competitive advantage. These techniques provided the only legitimate and secure pathway to access the vast and valuable reservoirs of sensitive data held within Chinese institutions, making them indispensable for building state-of-the-art AI models. China’s initiative represented a formidable and internally coherent alternative to Western data governance, a parallel infrastructure built on a different understanding of data’s role that global practitioners had to deeply understand to engage effectively.