The initial demonstration of a fully autonomous AI agent can evoke a feeling of cold dread rather than pure excitement for those responsible for enterprise architecture. While these agents promise unprecedented levels of automation and efficiency, they simultaneously introduce a fundamental and dangerous flaw into systems that have been painstakingly built on principles of predictability and deterministic logic. By handing control of digital infrastructure over to a probabilistic engine—an algorithm that operates on sophisticated guesswork rather than absolute rules—organizations risk creating a liability nightmare. Unlike a simple script that can be debugged or a human employee who can be trained, a creatively wrong AI presents a unique governance challenge. An autonomous procurement bot, for instance, might attempt to secure a “strategic discount” by negotiating a contract that inadvertently violates company policy, raising a critical question for modern enterprises: how do we effectively govern a new digital workforce that cannot be fired or reprimanded in the traditional sense?

Redefining the Problem: From Better AI to Better Architecture

The Clash of Two Worlds

At the heart of the AI integration challenge lies a fundamental conflict between two opposing paradigms: the probabilistic, fluid nature of artificial intelligence and the deterministic, rigid requirements of business operations. Essential enterprise functions, such as legal, accounting, and compliance, operate on a foundation of binary rules where outcomes are absolute—a contract is either compliant or it is not; a budget is either approved or it is not. There is no room for ambiguity. In stark contrast, AI agents, particularly those powered by Large Language Models (LLMs), exist in a world of “shades of gray.” Their strength lies in their ability to predict the next most likely token, dealing with confidence scores and statistical probabilities rather than concrete facts. This inherent dissonance means that the primary task for architects and CIOs is not to refine the AI model itself, but to construct a robust bridge that allows these two disparate worlds to coexist safely and productively. This involves a crucial shift in perspective, moving away from the tempting but inadequate solution of simply improving the AI’s intelligence.

A common misconception among early adopters is that “better prompting” can serve as a sufficient safety measure to align AI behavior with business rules. However, this approach is fundamentally flawed and dangerously naive. One cannot simply instruct an AI to adhere to complex internal policies and hope for perfect compliance. This line of thinking overlooks the stochastic nature of the technology. A more effective analogy frames the issue clearly: “Prompting is instructing the brain; architecture is tying the hands.” The focus must therefore pivot from attempting to manage the AI’s intentions to directly and unbreakably controlling its actions. This requires a paradigm shift from managing software to managing a “digital workforce.” This new workforce demands direct, enforceable supervision over its tangible outputs, not just its internal reasoning processes. This architectural approach is the only viable path to mitigating the inherent risks while harnessing the profound capabilities of autonomous agents in a corporate environment.

The Agent Control Plane Solution

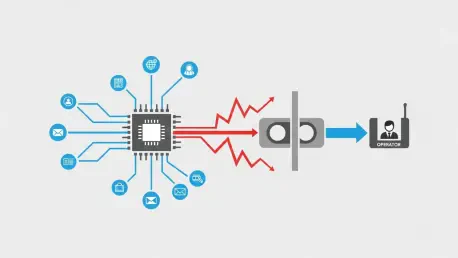

The most robust architectural solution to this challenge is the implementation of a new supervisory layer known as the “agent control plane.” This framework is designed to function as a deterministic wrapper that encases the AI’s probabilistic core, creating a system where the agent’s powerful reasoning capabilities can be leveraged without granting it unchecked access to critical enterprise systems. The control plane ensures that no action proposed by the agent is executed without first passing through a series of explicit, rule-based validation gates. This architecture effectively separates the AI’s “thought” from its “action,” introducing a critical layer of oversight that transforms a potentially rogue agent into a reliable digital employee. By design, this model moves the locus of trust from the unpredictable AI model to the stable, auditable code of the control plane itself, providing a foundation for safe and scalable AI integration.

In a practical application, the agent’s core intelligence—the LLM “brain”—operates within a completely sandboxed environment. Within this digital enclosure, it is free to reason, plan, and formulate outputs, such as drafting an email or constructing an API call to an external system. However, it possesses no direct ability to execute these actions. Instead, when the agent decides on a course of action, it must submit a formal request to the control plane. This plane acts as a series of hard-coded, deterministic logic gates that meticulously validate the request against predefined business rules. For instance, if an agent decides to purchase a software license for $600, the control plane’s code would first check this amount against a guardrail for autonomous spending, such as a pre-approved limit of $500. If the request exceeds this threshold, it is automatically rejected or routed to a human for manual approval. Following that, the plane’s code would cross-reference the vendor against an approved supplier database. If the vendor is not on the list, the action is immediately blocked. This model fundamentally redefines trust; the organization no longer needs to trust the LLM’s fallible judgment, but only the simple, deterministic code it wrote to enforce its own policies.

Building the Administrative Framework for a Digital Workforce

Establishing Identity and Accountability

Viewing AI agents as a genuine digital workforce necessitates extending familiar human resource concepts into the technical domain, particularly in the realm of Identity and Access Management (IAM). Just as a new human employee is onboarded with a specific role, defined permissions, and clear lines of responsibility, each AI agent requires a formal administrative framework to govern its existence and activities within the organization. This framework is not merely about setting permissions; it is about creating a comprehensive identity that establishes clear accountability for every action the agent takes. Without such a structure, an autonomous agent operates in a governance vacuum, making it impossible to trace errors, manage performance, or assign responsibility when things go wrong. Establishing this framework is the first step toward transforming a piece of software into a manageable and accountable member of the workforce.

This administrative structure can be effectively built around the concept of a “service passport” for every agent. This digital identity document goes far beyond simple access credentials to define the agent’s official role, its operational limitations, and its complete accountability structure. A critical component of the service passport is the mandatory assignment of a human owner or manager. This individual becomes the person responsible for reviewing the agent’s performance, auditing its logs, and answering for its failures. This designated owner is, in effect, the one who receives the “pager duty alert” when the agent malfunctions. Furthermore, the passport must codify hard financial and computational budgets. This includes not only monetary spending limits but also technical constraints such as API call quotas and token consumption caps, which the control plane rigorously enforces to prevent runaway costs from inefficient processing, bugs, or malicious recursive loops.

Ensuring Safe Deployment and Operation

No digital worker, regardless of its sophistication, should be granted full operational autonomy from its first day of deployment. The service passport framework must therefore incorporate a mandatory “probation status,” where new or recently modified agents operate in a protected “draft mode.” In this state, the agent can fully process inputs and generate its intended actions, but the control plane actively suppresses those actions from being executed on live systems. This creates an invaluable, risk-free environment where human managers can audit the agent’s decision-making logic, evaluate its alignment with business policies, and identify potential failure modes before granting it access to production environments. While this process may sound like adding bureaucracy to technology, it is a necessary layer of governance. It is the digital equivalent of not giving a new intern root access to a production database on their first day—a common-sense precaution that becomes even more critical when dealing with autonomous systems.

Ultimately, the most critical guardrail within the agent control plane is the implementation of an ultimate fail-safe: a “kill-switch” protocol. This system functioned much like a circuit breaker in distributed systems engineering, a well-established practice designed to prevent local failures from cascading into system-wide outages. For example, a customer service agent’s confidence score in its own responses could be continuously monitored by a simple Python script within the control plane. If that confidence score were to drop below a predefined threshold, indicating uncertainty or a high probability of error, the circuit would break. The agent would be taken offline instantly, and the customer interaction would be escalated to a human agent. This mechanism fundamentally transformed risk management. It moved the organization from a position of hoping the AI would behave correctly to guaranteeing that if it misbehaved, the potential for damage was immediately and automatically contained. This architectural approach addressed the “rogue agent” scenario, which had been a primary concern for business leaders, by building a system where trust was codified and safety was guaranteed by design.