Chloe Maraina is passionate about creating compelling visual stories through the analysis of big data. She is our Business Intelligence expert with an aptitude for data science and a vision for the future of data management and integration. In our conversation, we explore the critical, often-overlooked foundations of successful AI adoption. We’ll move past the hype to discuss why so many initiatives stall in “pilot purgatory” and how to ground them in tangible business outcomes. Chloe will share her insights on building a robust data culture, the indispensable role of human judgment in an automated world, and the strategic importance of creating a centralized AI Center of Excellence to navigate the complex risk landscape.

The article stresses starting with a clear business outcome rather than the technology. Can you walk me through the process of creating a strong business problem statement for an AI initiative? Please share an example of a vague goal and how you would refine it into a strategic, actionable one.

Absolutely. This is the most common pitfall I see. Teams get excited about the technology and start with a vague goal like, “We want to use AI to improve customer service.” That’s not a strategy; it’s a wish. It doesn’t tell you what to measure, what data you need, or what success even looks like. The first step is to slow down the conversation and insist on discipline. I encourage teams to isolate a specific, painful problem. So, we’d take that vague goal and ask pointed questions: Where are we failing our customers most often? Is it response time? Is it first-call resolution? Let’s say we discover our biggest issue is that customers get bounced between three different agents before their problem is solved. Now we can refine that statement. The vague goal becomes a strategic one: “We will implement an AI-powered routing system to analyze incoming customer queries and direct them to the agent with the precise expertise needed, aiming to increase our first-call resolution rate by 20% within six months.” See the difference? It’s specific, measurable, and directly tied to a business outcome. It gives the team a clear target and helps us separate the shiny new tech from a truly strategic solution.

A McKinsey survey noted that nearly two-thirds of companies struggle to scale AI beyond pilot programs. Based on your experience, what are the primary reasons for this “pilot purgatory,” and what key checkpoints should a team implement to ensure a project can successfully mature and be deployed widely?

That “pilot purgatory” is a place I’ve seen far too many promising projects die. The primary reason, almost every time, is that the pilot was built on a shaky foundation. Teams often try to build a sophisticated model on fragmented, messy data, hoping the AI will magically clean everything up. But AI is an amplifier; it will only amplify the inconsistencies and lead to unreliable outcomes. Another reason is the lack of a clear, measurable business case from the start. A pilot might look exciting in a controlled environment, but if you can’t justify the investment to scale it, it’s dead on arrival. To avoid this, teams must implement rigorous checkpoints. First, before you even write a line of code, you must define the success metrics. How will you know this is working? Second, I advise instituting regular 30- or 45-day check-ins. These aren’t just status updates; they are honest assessments. Is the project still aligned with our business objectives? Are we seeing the expected results, even at a small scale? If the answer is no, you have to be willing to reassess or even walk away. These checkpoints force a discipline that is crucial for ensuring a project has the legs to move from a cool experiment to a widely deployed, value-generating tool.

The text highlights data quality, consistency, and context as major barriers. When an organization decides to build a “single source of truth” data fabric, what are the first three practical steps they should take? Could you also share some metrics for measuring the success of this effort?

Building a “single source of truth” is less of a technical project and more of a cultural transformation, but it starts with practical, concrete steps. The very first step is to establish clear ownership. At one company I worked with, Reworld, they assigned data stewards to each domain. This creates accountability. You need someone who is responsible for the quality and integrity of data in their specific area. The second step is to create a living data dictionary. This isn’t a dusty document in a forgotten folder; it should be a searchable, accessible resource that defines every piece of data, including its lineage—where it came from, how it’s used, and who owns it. This builds trust. The third step is to automate quality control at the point of ingestion. You must standardize schemas and enforce data contracts so that messy, inconsistent information is caught before it ever pollutes your ecosystem. As for measuring success, you can track metrics like a reduction in data-related errors reported by business units, an increase in the self-service usage of analytics dashboards—which shows people trust the data—and a decrease in the time it takes for data science teams to prepare data for modeling. Ultimately, the biggest metric is confidence. When your teams stop questioning the data and start using it to make bold decisions, you know you’re succeeding.

You mentioned the importance of creating an AI Center of Excellence with security involved from the start. Beyond IT and security, who are the essential members of this group? Please share an anecdote about how this early, cross-functional collaboration helped prevent a significant risk or strategic misstep.

An AI Center of Excellence, or CoE, must be a cross-functional powerhouse. Beyond IT and security, it’s absolutely critical to include business leaders who understand the strategic goals, legal and compliance specialists who know the regulatory landscape, and, most importantly, the people whose daily work will actually be affected by the AI. Their domain expertise is invaluable. I remember one initiative where a company was developing an AI tool to help with financial approvals. The model looked great on paper. But because we had a compliance expert in the CoE from day one, she immediately flagged that the data set being used for training could inadvertently create a model that discriminated against certain applicants, which would have put the company in massive legal jeopardy. Security also pointed out that the way the data was being passed to the model created a vulnerability. If we had waited to bring in legal and security after the fact, we would have built an entire system that was not only risky but fundamentally unusable. That early collaboration didn’t just bolt on guardrails at the end; it helped us design a safer, more effective, and compliant solution from the ground up, saving months of rework and preventing a potential disaster.

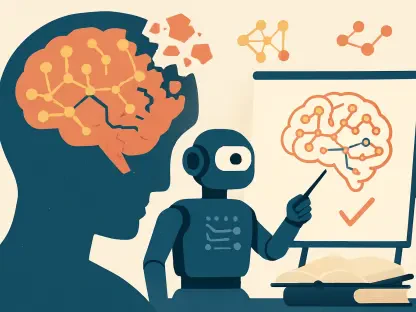

The Reworld anecdote about its lead qualification pilot failing without human review was very insightful. Can you describe a framework for designing effective human-in-the-loop systems? How do you determine the right balance between AI automation and human judgment to ensure the model continuously improves?

That anecdote is a perfect illustration of the goal: AI shouldn’t replace people, but rather create a partnership where each strengthens the other. A framework for an effective human-in-the-loop system begins with acknowledging that the model is a student, not a master. In the initial phase, you might have the AI shadow the human expert, making recommendations that the person can approve or reject. Every single correction the human makes is captured as valuable training data. For example, in that lead qualification pilot, after realizing the AI was ineffective alone, they retuned it so that human feedback was constantly fed back into the system. This creates a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement. The balance between automation and judgment is determined by the cost of being wrong. For low-stakes decisions, like categorizing internal documents, you can lean more heavily on automation. But for high-stakes decisions, like medical diagnoses or large financial transactions, human validation must remain a non-negotiable final step. The system is designed to evolve; as the model becomes more accurate—say, hitting a 99% accuracy rate on a certain task—you can gradually increase its autonomy for that specific task, freeing up the human expert to focus on more complex, nuanced challenges that still require their intuition and judgment.

The idea of 30- or 45-day checkpoints to reassess AI projects is a great discipline. What specific success metrics should leaders review at these meetings? Can you walk me through a time you had to make the difficult decision to stop an initiative and how you communicated that choice?

At these checkpoints, leaders need to look at a dashboard of both technical and business metrics. On the technical side, you’re reviewing model accuracy, data drift, and processing speeds. But more importantly, you must review the business metrics you defined at the very beginning. Are we seeing a leading indicator of our target outcome? If the goal is to increase sales, are we seeing an uptick in qualified leads or conversion rates in our pilot group? You also need to assess alignment—is this project still the most strategic use of our resources, or has the market shifted? I was involved in a project once to predict equipment failure in a manufacturing plant. The initial model was promising, but at our 90-day checkpoint, we realized the data from the legacy sensors was simply too inconsistent. We were spending 80% of our time trying to clean the data and only 20% on the model. The projected ROI was shrinking every week. It was a tough call, but we decided to halt the project. When communicating this, it’s crucial to frame it not as a failure, but as a strategic decision. We explained to the stakeholders that proceeding would be irresponsible and that we were reallocating that brilliant team to a different project with a higher probability of success based on what we had learned. It’s about being honest and making smart choices, even when it means shelving something you were excited about.

The article connects verifying data lineage to mitigating bias. Could you elaborate on this connection? Please outline a step-by-step process a team can follow to vet a dataset for both its provenance and potential biases before it’s used to train a model.

The connection is profound. Bias doesn’t just appear in an algorithm; it’s almost always a reflection of biases present in the data it was trained on. Verifying data lineage—its provenance—is like being a detective investigating the scene before the crime. You have to understand where the data came from and how it was collected, because that context is where bias often hides. If a dataset for loan applications was collected from only one geographic region, its lineage will tell you that, and you’ll know it’s not representative. A step-by-step process for vetting would look like this: First, establish provenance. You must answer: who collected this data, when, and for what original purpose? Second, review all available documentation. This can reveal the methods used for collection or transformation, which might introduce bias. Third, perform rigorous data quality checks for completeness, accuracy, and consistency. Incomplete demographic data, for example, is a huge red flag. Fourth, apply quantitative fairness metrics. You can run statistical tests for things like disparate impact to see if the data, and by extension the model, would treat different groups inequitably. Finally, bring in the domain experts. They have the contextual understanding to spot biases that automated tools might miss. They can look at the data and say, “This doesn’t feel right; it doesn’t reflect the reality I see every day.” It’s this multi-layered vetting process, combining technical rigor with human wisdom, that gives you the best chance of building fair and responsible AI.

What is your forecast for the future of AI and data strategy?

My forecast is that the conversation will mature significantly. For the past few years, it’s been a frantic gold rush, with companies chasing the technology for technology’s sake. I believe we’re entering an era of pragmatism. The successful enterprises won’t be the ones with the flashiest algorithms, but the ones with the most disciplined data culture. The focus will shift from “building AI” to “solving problems with AI,” which is a subtle but critical distinction. We’ll see a much deeper appreciation for the ‘unsexy’ work of data governance, lineage, and quality, as organizations realize that’s the true competitive advantage. Furthermore, I predict that human oversight and ethical frameworks will become embedded in the AI development lifecycle, not as a compliance checkbox, but as a core design principle. The future isn’t about autonomous machines making every decision; it’s about creating powerful partnerships between humans and AI, where technology handles the scale and speed, and people provide the wisdom, context, and ethical judgment. The companies that master this symbiotic relationship are the ones that will thrive.