In the critical, high-stakes world of child welfare, where caseworkers’ decisions can irrevocably alter the course of a child’s life, the slow embrace of artificial intelligence presents a profound and troubling paradox. For years, proponents have championed predictive risk models—sophisticated algorithms designed to analyze data and identify children at high risk of harm—as a transformative tool. These technologies promise to bring a new level of objectivity and efficiency to a system often overwhelmed by immense caseloads and reliant on subjective human judgment. Despite successful pilot programs in pioneering jurisdictions and a push from federal bodies to modernize, the vast majority of child welfare agencies across the United States remain hesitant, continuing to operate with legacy systems and traditional methods. This gap between the potential of AI and its practical implementation is not the result of a single obstacle but a complex web of technological deficiencies, financial constraints, and deep-seated ethical debates that question the very fairness of data-driven decision-making in protecting the nation’s most vulnerable children.

The Promise of Data-Driven Decision-Making

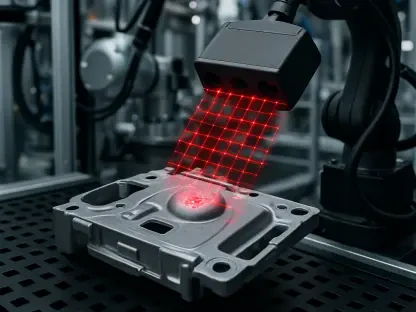

At its core, predictive analytics in child welfare is designed to augment human expertise rather than replace it, offering a powerful tool to navigate the complexities of risk assessment. These models function by processing vast and varied datasets, which can include a family’s history with the criminal justice system, records of hospital visits, previous interactions with social services, and reports of substance abuse. By applying machine learning algorithms to this historical information, the system identifies subtle patterns and correlations that may be invisible to the human eye, ultimately generating a “risk score.” This score serves as an analytical guide, quantifying the statistical likelihood of future maltreatment and helping caseworkers and their supervisors pinpoint the cases that demand the most immediate and intensive attention. The intention is to move beyond intuition-based assessments, which can be inconsistent and prone to unconscious bias, toward a more structured, evidence-based approach that ensures resources are directed where they are needed most.

The primary benefit articulated by early adopters is the model’s capacity to provide a crucial check against the inherent limitations of human judgment, particularly in high-pressure situations. As Erin Dalton, a leader in Allegheny County’s Department of Human Services, has noted, gut feelings are often not reliable predictors in this field. Predictive tools are engineered to compel caseworkers to “pause a little bit and take a more holistic view,” surfacing potential risk indicators that might otherwise be overlooked during a rapid assessment. This data-driven insight empowers agencies to manage their caseloads more effectively and strategically deploy preventative services to families before a situation escalates to a crisis. Evidence from a randomized controlled trial conducted by Duke University economist Jason Baron in Pennsylvania validated this approach, demonstrating that the use of these models led to a tangible reduction in re-referrals for child welfare concerns. This finding suggests that when used as a complementary tool, the technology can lead to demonstrably better outcomes and enhanced safety for children.

The Concrete Barriers to Implementation

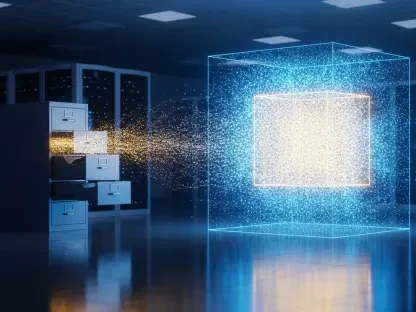

Despite the compelling potential of predictive analytics, a formidable barrier to widespread adoption lies in the antiquated technological infrastructure that plagues most child welfare agencies nationwide. A comprehensive report from the National Association of Counties painted a bleak picture of systems hobbled by aging software, outdated data storage, and fragmented case management tools that do not communicate with one another. This technological disarray creates significant inefficiencies, frustrating caseworkers and slowing down critical processes. More importantly, it creates an environment where implementing a sophisticated data model is nearly impossible. For a predictive algorithm to function effectively, it requires access to clean, comprehensive, and integrated data from across multiple systems. When data is trapped in isolated silos, as is often the case, the essential fuel for the analytical engine is unavailable, rendering the technology impotent from the start and halting progress before it can even begin.

This foundational issue of poor infrastructure is directly linked to a pervasive and legitimate fear of the “garbage in, garbage out” principle. Many state and local agency leaders are reluctant to invest significant resources in predictive models because they lack confidence in the quality and integrity of their own data. If the historical data used to train an algorithm is incomplete, inaccurate, or reflects past biases, the model’s predictions will be unreliable at best and discriminatory at worst. This concern is validated by federal officials like Alex Adams, Assistant Secretary for the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), who has acknowledged that the data infrastructure is so outdated that official reports on state child welfare systems are often two years out of date. This significant lag makes it “almost impossible to make good, data-driven, evidence-based decisions.” This challenge is further compounded by severe financial constraints. Without dedicated federal funding or an enhanced federal match, already under-resourced local agencies simply cannot afford the massive capital investment required to overhaul their legacy systems and build the modern data platforms necessary for AI implementation.

The Ethical Tightrope of Bias and Surveillance

Beyond the significant practical and financial hurdles, a profound and complex ethical debate contributes to the slow adoption of predictive analytics in child welfare. A critical report from the United Nations has amplified a major concern: that these data-driven, surveillance-based tools risk disproportionately targeting and penalizing families based on their socioeconomic status and race. The report highlighted that over 75% of children removed from their homes in the U.S. are taken for reasons of “neglect,” a term that can be nebulously defined and is often conflated with the conditions of poverty, such as unstable housing, food insecurity, or a lack of access to medical care. Critics fear that predictive models, trained on historical data that inevitably reflects these deep-seated societal biases, will simply learn to equate poverty with risk. The danger is that the technology could automate and amplify existing discrimination, flagging families for being poor rather than for being a genuine danger to their children, thereby turning a tool meant to protect into one that punishes vulnerability.

In response to these valid ethical concerns, proponents of the models offer a robust counterargument, contending that when properly designed and implemented, these tools can help to mitigate, rather than exacerbate, the impact of human bias. They argue that while historical data is imperfect, a well-constructed algorithm can be more consistent and less susceptible to the implicit biases that can unconsciously influence a caseworker’s judgment. Erin Dalton asserted that in Allegheny County, the predictive tool has helped workers make “less biased decisions than gut alone.” This claim is supported by researchers like Jason Baron, who noted that safeguards are routinely implemented, such as explicitly excluding race as a predictive variable in the algorithm. His findings indicated that the models did not lead to an increase in racial disparities in foster care placement rates. The consensus among these experts is that the true risk lies not in the technology itself, but in how it is used. The key is to treat the algorithm’s output as one piece of information among many, a prompt for deeper inquiry rather than a directive for action.

Forging a Path Toward Modernization and Prevention

The slow progress in adopting predictive risk models was ultimately understood not as a failure of the technology itself, but as a symptom of deeper systemic issues. It became clear that successful and ethical implementation depended on a broader overhaul of the child welfare system. The path forward required a unified vision, championed by federal partners like the Administration for Children and Families, which centered on two interconnected goals. The first was a fundamental philosophical shift away from a reactive system focused on investigation and removal and toward a proactive one centered on prevention and family support. As leaders like Idaho’s Lance McCleve emphasized, the ultimate purpose of using these tools was to reduce the number of families cycling through the system by identifying needs early and providing preventative support, such as substance abuse counseling and after-school programs. This approach aimed to minimize the trauma of family separation by addressing root causes before they escalated into a crisis.

This philosophical shift was paired with a second, equally critical component: a concerted, federally supported effort to modernize the nation’s child welfare data infrastructure. Leaders like ACF Assistant Secretary Alex Adams spearheaded reforms to the national reporting structure, pushing for data collection that could “truly capture the safety, well being of children” in a more timely and holistic manner. Initiatives like “A Home for Every Child” signaled a recognition that local agencies could not solve this monumental challenge on their own. The solution demanded a combination of dedicated funding for technology upgrades, robust technical assistance, and a shared commitment across all levels of government. Building a data-driven system that was not only more efficient but also more equitable and focused on preserving families became the accepted blueprint for moving forward, ensuring that technology served as a tool for strengthening communities rather than just identifying their risks.